Only a few herds of reindeer and caribou are increasing or are stable at high numbers; most herds continue to decline or remain at low numbers after severe declines in recent decades. Whether these trends are a result of Arctic climate change or part of a natural pattern is still unknown.

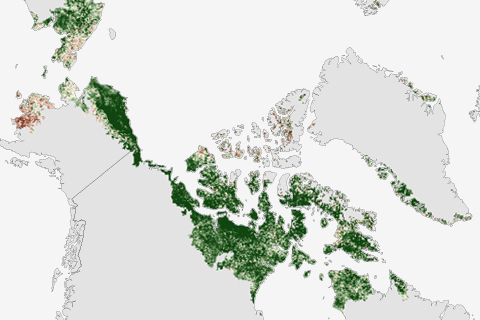

Since observations began in 1982, Arctic-wide tundra vegetation productivity has increased. In North America, the rate of greening has accelerated since 2005.

Since the early 1990s, annual atmospheric equivalent black carbon concentrations in the Arctic have decreased at the surface by as much as 55 percent—one of the few "good news" stories coming out of the region.

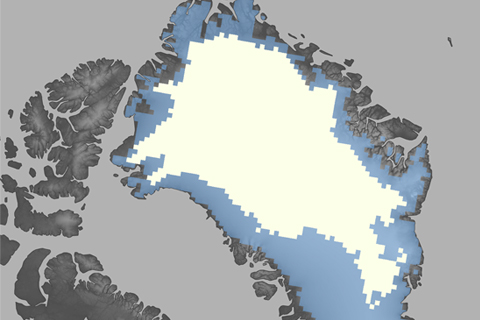

After record-breaking melt during the 2012 season, the 2013 melt extent was more on par with the long-term average. The reprieve from the record warmth and melting of the past six summers is likely connected to a strong positive phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation during summer 2013.

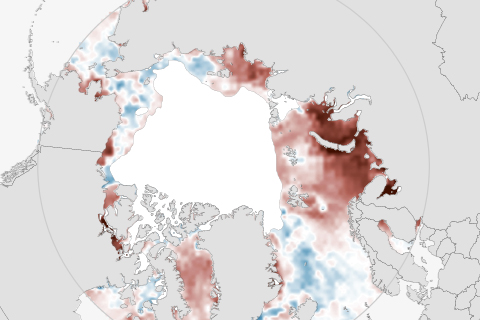

Most of the Arctic boundary waters were warmer than average in summer 2013, but a few cool pockets appeared in the western Arctic and the Greenland Sea. Warmer waters are drawing new species from lower latitudes into the Arctic.

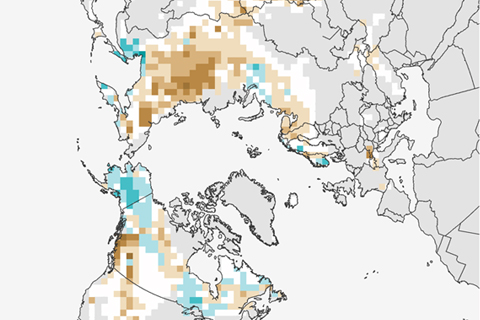

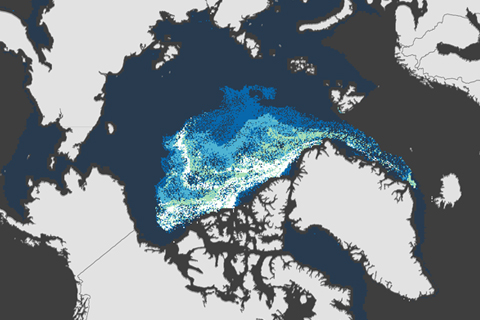

In May 2013, there was record-setting loss of Eurasian spring snow cover, and spring snow cover was below normal again in June—the fourth lowest on record. This is the sixth year in a row that Eurasia has set a new record low in either May or June snow extent.

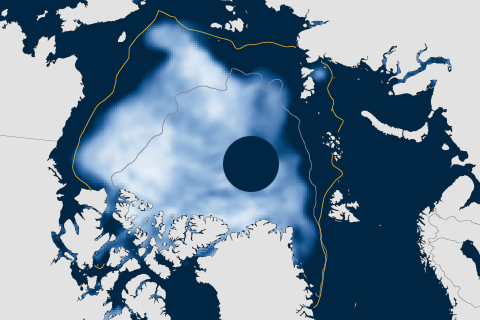

In March 1988, thick, multi-year ice comprised 26 percent of the Arctic's ice pack. In 2005, that number dropped to 19 percent. In 2013, it dropped to 7 percent.

Averaged over September 2013, sea ice extent was 2.07 million square miles—larger than last year's record low, but still more than 17 percent below average and the sixth smallest September extent on record.

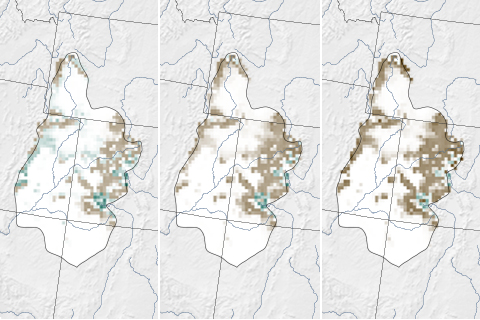

Models project that extreme dust events combined with global warming could advance the spring thaw in the mountains of the Upper Colorado River Basin by as many as 6 weeks by 2050. The earlier disappearance of snow could amplify water disputes, extend the fire season, and stress aquatic ecosystems.

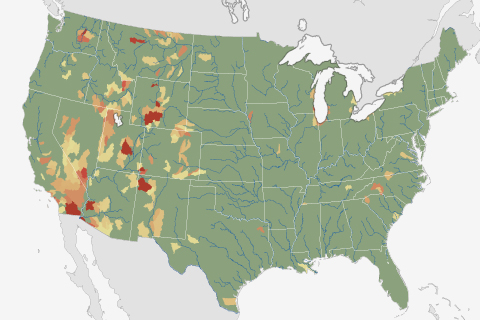

Nearly ten percent of U.S. watersheds are living beyond their means when it comes to their water supply. For nearly half the country, water stress is projected to worsen by mid-century because of climate change, according to a recent NOAA-funded analysis.