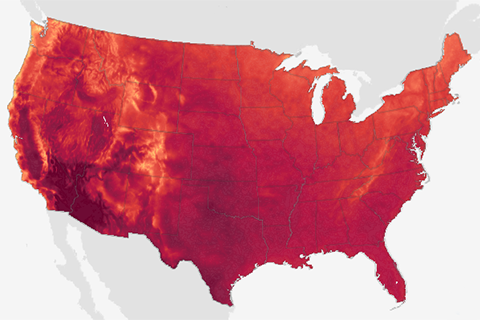

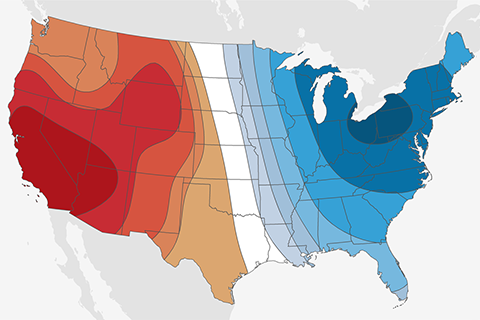

U.S. maps of average daytime high temperature in January, April, July, and October in the 2060s show the projected impacts of continued high emissions of carbon dioxide.

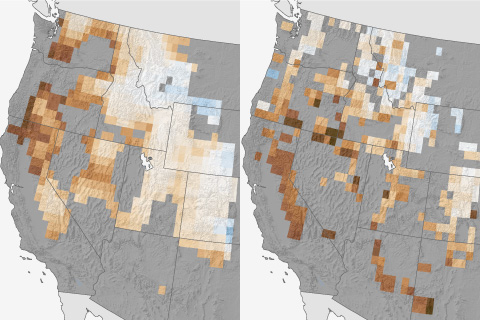

Test runs of experimental models for predicting winter snowpack show some success in many mountain ranges in the western United States.

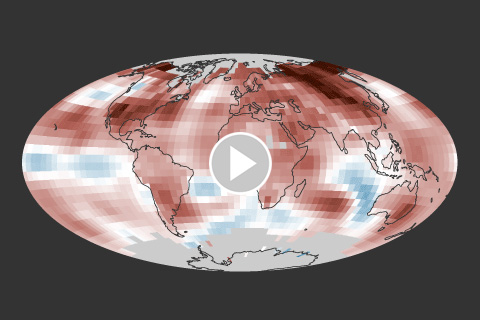

The 2017 average temperature was the third highest since 1880, behind 2016 (warmest) and 2015 (second warmest).

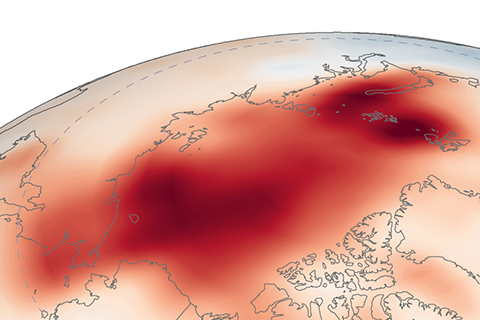

Groundfish stocks in the Eastern Bering Sea are healthy at present, but a recent string of very warm summers, preceded by winters with sparse sea ice, led NOAA biologists to recommend lower catch limits for pollock—the nation's largest commercial fishery.

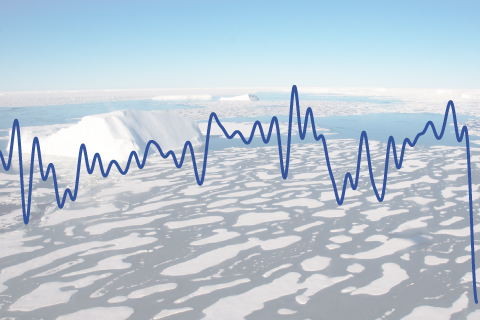

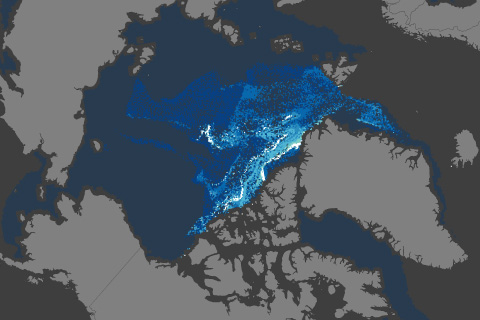

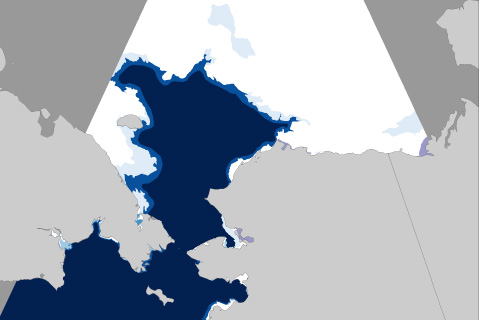

Paleoclimate records show that while there have been several periods over the past 1,450 years when sea ice extents expanded and contracted, the decrease during the modern era is unrivaled.

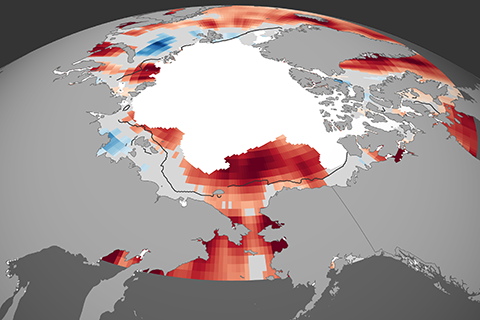

Since 1982, the rate of surface warming in some Arctic seas at the height of summer is more than quadruple the rate of warming in the global ocean.

Very old ice—thick, strong, and more melt-resistant—has nearly vanished in the Arctic. In March 2017, it made up less than 1 percent of the ice pack.

Spring and summer temperatures in the Arctic were cooler in 2017 than they have been in many years this decade, but the annual average surface temperature was still the second highest on record.

The most recent 8-14 day outlook for the United States predicts a turn towards wintry temperatures across the eastern United States, but much warmer than average temperatures in the West.

Where winter sea ice should be starting to cover the ocean, thousands of square miles of open water stretch westward from Alaska across the Bering and Chukchi Seas in November 2017.