A series of unusually strong, long-lasting high pressure systems has parked over Greenland this summer. As many a weather forecaster has explained, high pressure generally leads to calm winds and sunny skies, both of which boost temperatures during the all-day sunshine of mid-summer at high latitudes. The conditions contributed to widespread melting of the ice sheet.

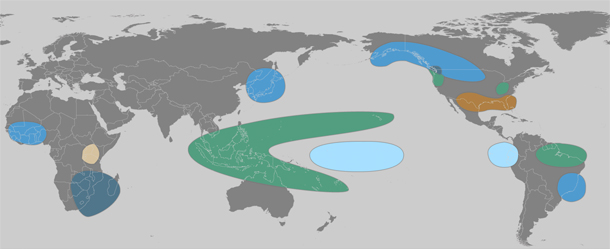

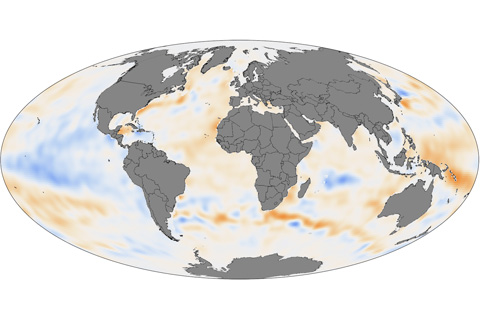

The lead character in the 2011 climate story was La Niña—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation—which chilled the central and eastern tropical Pacific at both the start and the end of the year. These natural cooling events have a long reach: many of the big climate events of 2011, including famine-inducing drought in East Africa, an above-average hurricane season in the Atlantic, and record rainfall in many parts of Australia, are common “side effects” of La Niña.

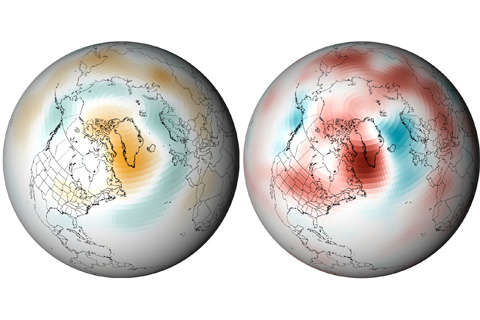

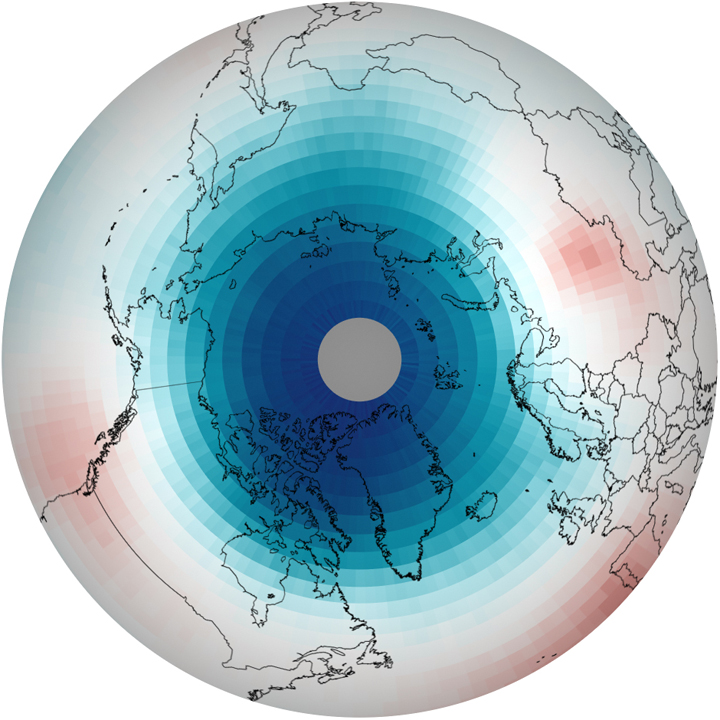

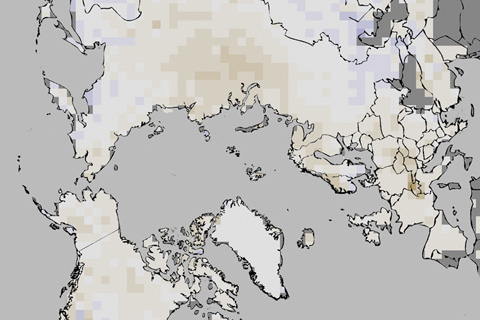

In the spring of 2011, scientists observed the largest, most severe ozone destruction ever witnessed in the Arctic since records began in 1978, due in part to the fact that CFCs stick around in the atmosphere for a very long time. Climate maps reveal the cause to be unusually persistent cold temperatures.

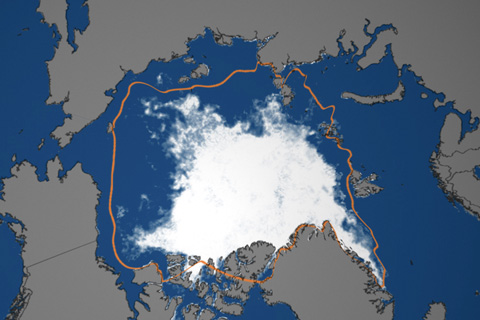

In September 2011, Arctic sea ice reached its second-lowest minimum extent in the satellite record.

Data from 2010 indicate that mountain glaciers predominantly lost mass, and preliminary data from 2011 indicate a continuation of the same long-term trend.

In early 2011, stratospheric temperatures rose over the tropics due to La Nina while temperatures over the poles fell below the long-term average.

In 2011, annual snow cover extent over Northern Hemisphere continents (including the Greenland ice sheet) averaged 24.7 million square kilometers, which is 0.3 million square kilometers less than the long-term average.

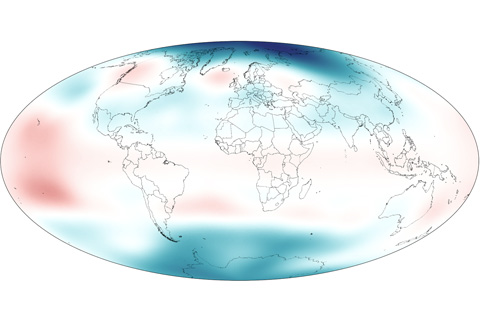

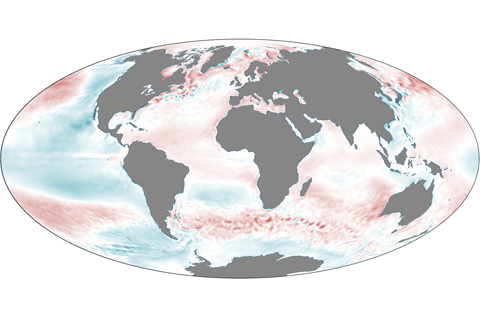

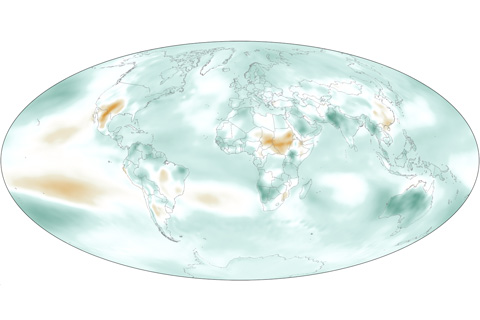

In 2011, La Niña and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation cooled parts of the Pacific Ocean, but unusually warm temperatures predominated elsewhere.

Except for some La Niña-cooled regions of the tropical Pacific and a few other cool spots, the upper ocean held more heat than average in 2011 in the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, and Southern Oceans.

In 2011, Earth’s atmosphere was cooler and drier than it had been the previous year, but it was more humid than the long-term average.