Active Atlantic hurricane eras come with a speed bump for storms that approach the U.S.

Details

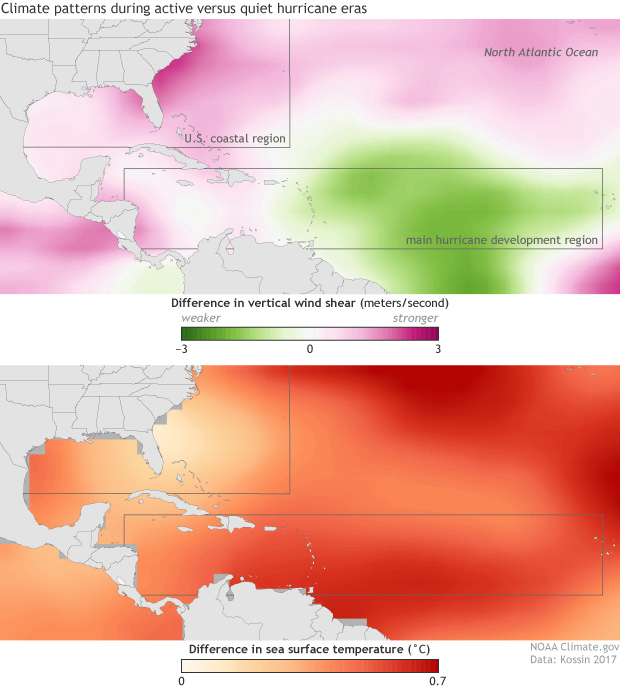

The hurricane record from the Atlantic Ocean shows phases of high and low activity that can last several decades at a time. Active eras spawn more hurricanes per season on average, especially major hurricanes. All else being equal, more major hurricanes overall ought to mean more major hurricane landfalls in the United States, but records show that isn’t the case. These maps show one possible explanation for that puzzle: otherwise active hurricane eras appear to have a built-in speed bump for major hurricanes that approach the U.S.

Based on research by NOAA hurricane expert Jim Kossin, these maps show the difference in vertical wind shear (top) and sea surface temperature (bottom) between the current active hurricane era (1993-2015) and the previous quiet period (1970-1992). Across most of the tropical Atlantic (where hurricanes form), average climate conditions since the mid-1990s have been especially friendly to hurricanes, with higher ocean surface temperatures (darker reds) and weaker vertical wind shear (greens). But over the Gulf of Mexico and off the U.S. southeastern seaboard, the pattern is reversed: cooler temperatures (relative to the main development region) and stronger vertical wind shear, both of which weaken hurricanes.

On the one hand, this might seem like a stroke of amazingly good luck—just when the country would otherwise be at higher risk of a major landfalling hurricane, the climate system offers up some built-in protection. Unfortunately, this shiny penny has a tarnished flip side. During the quiet era, hurricanes that did approach the United States—especially major hurricanes—were more likely to intensify rapidly.

As the maps show, areas near the U.S. coast tended to be warmer during the quiet period, and the wind shear tended to be weaker. While the average number of hurricanes that formed per season across the entire Atlantic basin was lower during the quiet era, the ones that did approach the United States were more likely to encounter very hurricane-friendly conditions. This relationship also showed up in comparisons between the 1970-1992 quiet era and the active period that preceded it from 1947-1969.

Kossin found that during the quiet period, a major hurricane near the U.S. coast was 3-6 times more likely to intensify by 15 knots within 6 hours than it was during the active periods. Unfortunately, Kossin points out, “Rapid intensification near the coast poses a very significant risk because it is difficult to forecast and shortens public warning time.”

Whether this pattern favoring rapid intensification near the U.S. coast will re-emerge when, or if, the Atlantic basin enters the next quiet era is not certain, of course. The comprehensive hurricane record is less than a century in length, which means that we have only have a few of these decades-long phases to study.

Experts are not even certain these active versus quiet phases are entirely natural; the drop in hurricane activity during the quiet period was probably partly due to air pollution particles, which can cool sea surface temperatures by blocking incoming sunlight. Cleaner air in the decades since may mean that the next “quiet” hurricane era won’t be as quiet as the past one. Factor in the possible influence of global warming, and the picture becomes even more uncertain.

Still, these results suggest that if another quiet era returns, coastal residents should be aware that lower storm numbers in the basin as a whole may mean greater risk when hurricanes approach the U.S. coasts.

References

Dunstone, N. J., Smith, D. M., Booth, B. B. B., Hermanson, L., & Eade, R. (2013). Anthropogenic aerosol forcing of Atlantic tropical storms. Nature Geoscience, 6(7), 534–539. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1854

Kossin, J. P. (2017). Hurricane intensification along United States coast suppressed during active hurricane periods. Nature, 541(7637), 390–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20783