Earlier this month, the California Fish and Game Commission closed the state’s year-round rock crab fishery north of the Ventura-Santa Barbara county line and delayed the opening of the lucrative recreational and commercial Dungeness crab fishery. The closures are the most recent of several that have occurred along the West Coast as far north as Washington as a result of potentially toxic levels of harmful algae.

Dungeness crab ready to eat at Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco, on March 26, 2005. Photo by Jon Sullivan, via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve already discussed previously the record-break algal bloom that is ongoing off the West coast of North America as well as how algal blooms normally develop. In both articles, I’ve mentioned that NOAA scientists and others are out in force monitoring this bloom and investigating its impacts and causes, including the potential influence of unusually warm water that has persisted along the West Coast virtually all summer and fall.

Scientists continue to analyze samples taken from cruises through the bloom dating back to last summer. Further research will have to definitively confirm the relationship between this year’s warm water and the record-breaking bloom.

In a recent news release from the Northwest Fisheries Science Center on the presence of algal toxins in marine wildlife, research biologist Kathi Lefebvre was quoted saying, “The findings suggest that unusually warm water off the West Coast in the past year led to a more toxic and widespread bloom, with greater impacts on marine wildlife.”

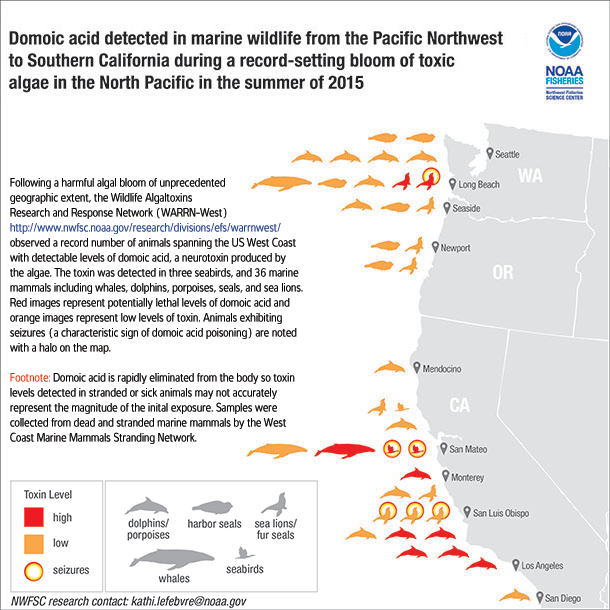

The algal toxin domoic acid was found in 36 marine mammals and three seabirds from southern California to the Pacific Northwest. Only a small fraction of the total number of stranded marine mammals coastwide were tested, but these findings indicate the large geographic range of the harmful algal bloom. The animals impacted ranged from dolphins, harbor seals, sea lions and whales to sea birds.

The domoic acid found in these animals is the result of the toxin traveling up the food chain to larger and larger predators.

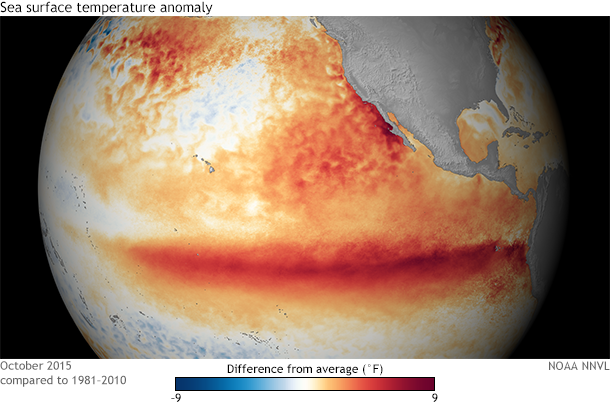

Ocean surface temperatures in October 2015 compared to the 1981-2010 average. Thanks to El Niño, the tropical Pacific is much warmer than usual, but so is the entire North Pacific along the U.S. West Coast. NOAA map by Dan Pisut, EVL.

When toxin levels rise to dangerous levels, domoic acid poisoning can cause seizures and death in marine mammals. Reports of seizures in several sea lions and sea birds have already been reported confirming that acute domoic acid poisoning has occurred in animals ranging from Southern California to Northern Washington.

The occurrence is the first time seizures and high domoic acid levels have been documented so far north. However, marine mammals face multiple stressors in addition to algal toxin exposure, and it is likely that many observed strandings are caused by a combination of factors.

Domoic acid in marine wildlife designated as high (red) or low (orange) based on previous surveillance data collected over several years. Animals exhibiting seizures are noted with an asterisk. Domoic acid is rapidly eliminated from the body of some animals so toxin concentrations detected in stranded animals may not accurately represent the magnitude of the initial exposure. Graphic by Kathi Lefebvre, Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

The number and geographical extent of recreational and commercial fishery closures also reveal the unusually widespread nature of this year’s harmful algal bloom. In addition to California’s closure of the Dungeness and rock crab harvests, Oregon’s recreational Razor Clam fishery remains closed as does the mussel fishery in southern Oregon from the Yachats River to the California border. Even as far north as Washington, recreational Dungeness crab fisheries within parts of Puget Sound have also been closed due to the presence of domoic acid.

The continuing presence of high levels of domoic acid in marine organisms does not necessarily mean that toxic algae is still present. The toxin lingers in the food chain as creatures that were exposed during summer retain toxins for months. It also reaches new organisms as one creature eats another, such as crabs that feed on bottom-dwellers, which in turn have fed on decaying blooms in the sediment.

It is important to note that commercial seafood remains safe to eat and in the United States, state public health agencies continue to monitor for dangerous toxin levels due to the ongoing bloom. As for what’s next, scientists will continue to research the causes and continuation of this record-breaking bloom, aware that there is a link between El Niño (which is occurring right now) and larger than usual blooms of Pseudo-nitzschia the following year (Trainer et al. 2000).

During a strong El Niño, above-average winter rainfall is usually observed across the state. This can greatly increase the amount of freshwater runoff into rivers and streams and eventually into the ocean. The runoff contains an increased amount of nutrients from the soil that can be flushed into coastal areas providing a beneficial environment for algae production.

Safe to say, this is an ongoing story, with chapters left to be written. We’ll keep providing updates in coming months.

References

Trainer VL, Adams NG, Bill BD, Stehr CM, Wekell JC, Moeller P, Busman M, Woodruff D (2000). Domoic acid production near California coastal upwelling zones, June 1998. Limnol Oceanogr 45:1818–1833