A large gap between treeline and the water level in California's Shasta Lake on August 25, 2014, is one sign of the state's devastating drought. Shasta Reservoir is at 30 percent of its total capacity and 47 percent of its historical average capacity. Photo credit: California Department of Water Resources.

Since we last covered the California drought, conditions in the state have stayed, well...dry—very dry. According to the California Department of Water Resources, the 2014 water year, which started October 1, 2013, and will end September 30, 2014, has so far been “one of the driest in decades and follows two consecutive dry years throughout the state." Statewide, total precipitation is about equal to or below the lowest three-year period since 1895.

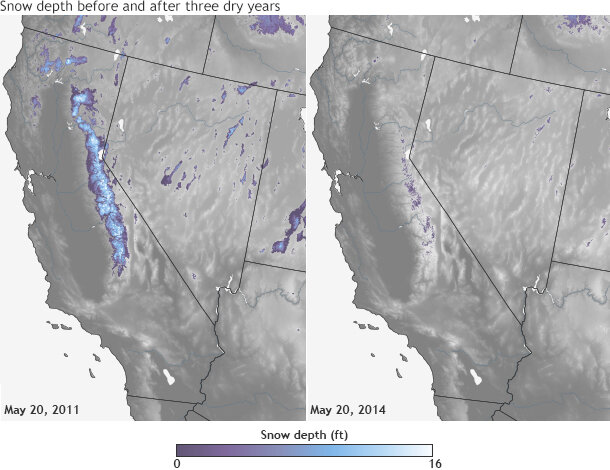

Spring snowpack conditions helped set the stage for a brutal summer. The fifth and final snow survey of the season in May 2014 recorded snowpack at only 18 percent of average statewide. By the end of the month, the Sierra snowpack water equivalent decreased to almost zero. Current reservoir conditions show most of the state’s reservoirs below 50 percent of their total capacity. Many are also below 50 percent of their historical average capacity.

The maps show snow depth as of May 20, 2011, and after three consecutive dry years on May 20, 2014. Deep snow is pale blue or white, and trace amounts are dark purple. Snow-free land is gray, and rivers and lakes are blue. Maps by NOAA Climate.gov, based on modeled snow depth data from the NOAA National Weather Service's National Operational Hydrologic Remote Sensing Center (NOHRSC) Snow Data Assimilation System (SNODAS).

large snow depth 5-2011 image | large snow depth 5-2014 image

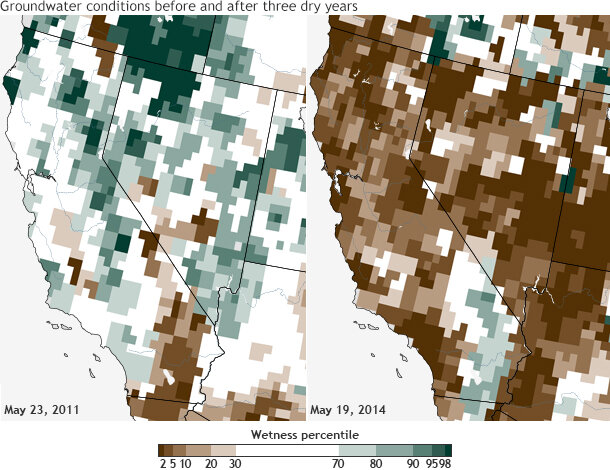

When surface water from snowpack-fueled rivers and reservoirs is running low, California’s natural reservoir of groundwater becomes vitally important. During a dry year, the Department of Water Resources estimates that groundwater, which is extracted from the ground through wells and pumps, provides close to 60 percent of the state’s water supply. Some communities in California are 100 percent reliant upon groundwater for urban and agricultural use regardless of whether it is a wet or dry year.

This year’s drought, according to a recent economic analysis published by the University of California, Davis, is estimated to “result in a 6.6 million acre-foot reduction in surface water available to agriculture”—a loss that will be partially replaced by increasing groundwater pumping by 5.1 million acre-feet. The missing 1.5 million acre-feet of water is estimated to cause losses of $810 million in crop revenue and $203 million in dairy and other livestock value, plus additional groundwater pumping costs of $454 million. These direct costs to California’s flourishing agriculture industry are estimated to total $1.5 billion.

Unfortunately for Californians turning to wells and pumps during dry times, possibly the greatest unknown for the state’s water future is its groundwater supply, says Kelly Redmond, Deputy Director and Regional Climatologist for the Western Regional Climate Center. "Very little is known about groundwater recharge and withdrawal rates for large sections of the state,” Redmond says. “[Groundwater is] completely unregulated; in general anybody can take whatever they have the resources to drill for.”

Groundwater is also not an everlasting or drought-proof resource. “In some places, like along the coast, the Central Valley, or in the southern valley basins, there isn’t much snow, so groundwater recharge comes mostly from rain,” Redmond explains. “In the higher mountains and farther north, snowmelt provides much of the recharge at higher elevations. Full rivers can also recharge along their corridors, through seepage into the surrounding substrate.”

A recent Drought Response report released on April 30 by the Department of Water Resources discussed some of these gaps in groundwater monitoring and the challenges researchers face in anticipating potential water shortages in groundwater basins.

Although there is some data on groundwater use, it’s far from adequate. The primary database, the Water Data Library, contains over 4,000 wells monitored under the California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring (CASGEM) Program and 39,429 voluntary wells—private wells whose owners have volunteered for groundwater level monitoring.

"Unfortunately, the record-keeping on groundwater pumping is terrible. ” Redmond says. “The database is riddled with small and large—and huge—errors, mostly unintentional, like gallons versus acre-feet. There is also motivation for not reporting groundwater usage, such as apprehension about further regulation.” The Department of Water Resources report pointed out that of California’s 515 alluvial groundwater basins, only 169 are fully or partially monitored.

Despite gaps in record-keeping, researchers are still able to conclude that groundwater usage has been huge, and more than previously thought. The report found that “groundwater levels have decreased in nearly all areas of the state since spring 2013, and even more notably since spring 2010.” Since spring 2008, groundwater levels have experienced all-time historical lows in most areas of the state, most notably in the northern San Francisco Bay hydrologic region, the southern San Joaquin Valley, and the South Lahontan and South Coast hydrologic regions.

In California’s San Joaquin Valley, so much water is being pumped from the ground that the land surface itself is subsiding, as many news reports have documented. The Valley is California’s top agricultural producing region, producing much of the nation’s grapes, nuts, and vegetables, and hosting three-quarters of the state’s dairy cows. According to the UC-Davis study, 70 percent of the statewide crop revenue losses, approximately 60 percent of the fallowed cropland and most of the dairy losses are likely to occur in the San Joaquin Valley, due to the expected net water shortage from the 2014 drought.

These maps show water stored in underground aquifers on May 23, 2011, and after three consecutive dry years on May 19, 2014, compared to the historical range for comparable weeks from 1948 to 2009. Areas where the groundwater storage was near the higher end of the historic range are shades of green while areas where the water storage (wetness percentile) was near the lower end of the range are shades of brown. Maps by Climate.gov, based on modeled groundwater indicator data from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE).

Since surface monitoring cannot provide the whole answer to how much of California’s groundwater is being used, scientists are turning to tools in the sky. NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite uses GPS and a microwave ranging system to map Earth's gravity field, detecting fluctuations in the gravity field connected to changes in the mass of water reserves below the surface.

In a recent study by NASA and the University of California, Irvine, researchers used monthly measurements of the change in water mass from the GRACE satellite to assess water loss in the Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to about 40 million people in seven states, including California. They found that since 2004, more than 75 percent of the water loss in the basin came from underground resources. The study’s findings suggest that the extent of groundwater loss may pose a greater threat to the water supply of the U.S. West than previously thought.

"In the end, to manage water effectively, we need to know all the components of the water budget,” Redmond says. “We need to keep pushing for the need to know these components in more detail, and for the tools to make the needed observations."

References

Howitt, R.E., Medellin-Azuara, J., MacEwan, D., Lund, J.R. and Sumner, D.A. (2014). Economic Analysis of the 2014 Drought for California Agriculture. Center for Watershed Sciences, University of California, Davis, California. 20p.

Stephanie L. Castle, Brian F. Thomas, John T. Reager, Matthew Rodell, Sean C. Swenson, James S. Famiglietti. Groundwater Depletion During Drought Threatens Future Water Security of the Colorado River Basin. Geophysical Research Letters, 2014.

Resources

EPA FY 2011-2014 Strategic Plan San Joaquin Valley

California Department of Water Resources