Details on the February ENSO Discussion: On the edge?

At the beginning of this month, we find ourselves looking at conditions in both the ocean and the atmosphere that appear a bit like El Niño. Sea surface temperature anomalies in the Niño3.4 region have been at or above +0.5°C for the last few months, and the forecast calls for a 50-60% chance the Niño3.4 index will remain above +05°C through the late winter and into spring. However, we still haven’t checked the box saying we have “El Niño conditions.” Why not?

Mostly, it's because even though there are some promising signs that the atmosphere may be responding to the warmer equatorial Pacfic, we've seen a lot of fluctuations over the past year. It will take more than a couple of weeks to convince us El Nino has really "locked in."

For the last few months, rainfall in the central equatorial Pacific has been less than average (as indicated by outgoing longwave radiation, see this post for more on that) - the opposite of what we’d expect to see from El Niño. During the last couple of weeks of January, that changed, and there was more rainfall than average around the Date Line. Related to these recent changes, the January Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (EQSOI) dropped to -1.0, after months of hovering around zero (negative EQSOI indicates a weaker Walker Circulation, often associated with El Niño).

Another indicator of possible El Niño conditions is the westerly wind anomalies that developed just east of the Date Line in the middle of January. And, to add to this El Niño sundae, yet another downwelling (warm) Kelvin wave has formed.

So what do we want, a cherry on top?

Here’s the cause for pause: all these signs have developed over just the past couple of weeks. El Niño is a climate phenomenon, meaning it is an average state over several months (or seasons), and not a short-term weather event. So, while all these signs are promising, we’d like to see them hang around for a little while longer before we declare El Niño conditions.

ENSO as a rock in a stream

Think of a rock sitting in a stream. The water bubbles and splashes, but generally goes around the rock, and its path is determined by the placement of the rock. But a couple of alternate scenarios could play out here. For example, under certain conditions the rock could move, and perhaps get pushed over to the other side of the stream and settle down there. The water in the stream would then have a different average path than it did before. Another possible scenario is the rock just rolls around in the stream and doesn’t settle at all. In that scenario, the stream's path would be constantly shifting, never settling into one pattern.

The atmospheric disturbance caused by El Niño is like a rock that influences where a stream flows. When the disturbance sets up in one place for long stretches of time, the flow of weather around becomes persistently altered. It takes more than a couple weeks for forecasters to tell whether the atmospheric disturbance is "settled in" or whether its more like a stone tumbling around in a stream. Photo by Emily Becker.

In this analogy, the rock is ENSO, and its state makes the weather (the water in the stream) more likely to flow one way or another. Right now, several pieces look favorable for a shift in conditions, but we want to see if the rock is just rolling around a bit, or if it’s more permanently settling into a new location. Over the past year, the stream has been winning, and the rock hasn’t settled.

It’s easy to look back on a period of time and see the overall pattern, rather than just the short-term fluctuations. During every El Niño event, there are times when the atmospheric conditions don’t reflect a weakened Walker Circulation. However, the idea is that the average over the lifetime of the event will show a tendency toward this atmospheric response. The tricky part for forecasters is determining if current conditions are just more fluctuations in the weather, or if they are part of a larger, longer-lasting climate pattern.

Time may be running out

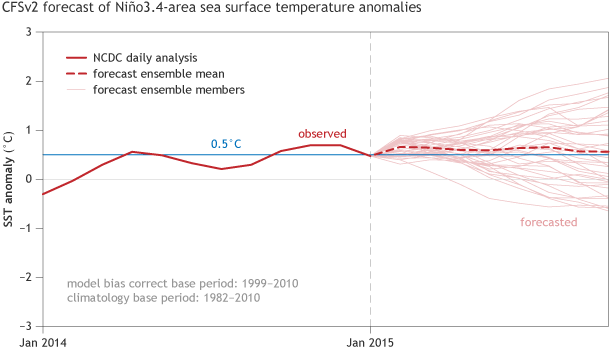

There are some other factors that are causing us to hesitate over the likelihood of El Niño emerging. For one thing, during the late winter and early spring it can be tough for the ocean and atmosphere to couple and reinforce each other because, climatologically, the east-to-west equatorial sea surface temperature (SST) gradients and winds become weaker as the Northern Hemisphere warms up. The model guidance suggests the positive Niño-3.4 SST anomalies will continue, but they increasingly show a wide variety of possibilities later in the year (Fig. 1).

Early February CFSv2 model forecast for average sea surface temperature anomalies in the Nino3.4 region.

Graph by Fiona Martin. Data from CPC.

Much like how forecasters didn’t declare the Dust Bowl drought over every time it rained, we’re not convinced we’re seeing El Niño conditions. The signs are there, though, and if they persist through the next month, we might very well have something different to say.

Comments

Question, when an El NIño has been declared in full in February

RE: Question, when an El NIño has been declared in full

It is hard to say because we have not always had operational monthly predictions of ENSO. Here is an archive of our forecasts going back to 2001:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/expert_assessment/ENSO_DD_archive…

And here is the ONI archive of ENSO episodes:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ens…

In that very short time span (relative to the history of ENSO, which has lasted for millions of years), CPC has never declared onset during March. But this is relatively meaningless because the ENSO cycle has varied over time. Even our observational record of Nino-3.4 index values going back to ~1950 is too short to really know for sure whether a March onset would be unprecedented. It is also not yet clear -- based on soley the ONI -- whether it would be sufficiently distinct from the warming that began in late 2014.

Below are our current probabilities for La Nina during 2015. While they are not zero, they are smaller than the chances of Neutral or El Nino:

http://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/?e…

el nino

RE: el nino

Hi Malik! Good question. Usually we associate El Nino with a decrease in cyclones in the Atlantic basin. However, ENSO conditions are just one of several factors to take into consideration.

As for the 2015 Atlantic Hurricane Season, it is too early to say. The Climate Prediction Center issues its pre-season Outlook at the end of May.

Feel free to look at the forecast for the 2014 Atlantic Hurricane Season to get an idea at what forecasters were looking at a year ago.

el nino and the RRR

Add new comment