Heat governance scholar Ladd Keith’s collaboration with NOAA

Introduction

Tucson, the hometown of NOAA-funded heat governance scholar Ladd Keith, Ph.D., is a metropolitan area of one million that still feels like a village. Keith knows it well; he attended grade school there and earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. at the University of Arizona. Brimming with culture and history, Tucson has a strong sense of place. Locals often talk about the university basketball team, Mt. Lemmon, the local food scene, bobcat sightings, and the timing of monsoon season. The stately saguaro cactus, celebrated in May Swenson’s poem, “Saguaros Above Tucson,” is an emblem of the city, the state of Arizona, and the entire Southwest region. “Saguaros, fuzzy and huggable, greet us, seeming to stream down the Rincon foothills as the car climbs,” reads Swenson’s poem. “Their plump arms branch, bend upward, enthused.”

A native of Tucson, NOAA-funded researcher Ladd Keith helps cities improve their resilience to extreme heat. Ladd is Assistant Professor of Planning, School of Landscape Architecture and Planning; and a Faculty Research Associate, at Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy. Photo courtesy Ladd Keith.

In the 1980s and 90s, when Keith was growing up, heat permeated Tucson life, but it wasn’t discussed much. “Day to day, it was not a topic that people said much about because it was just how things worked.” Like many others, Keith grew up with a swamp cooler, a relatively cheap, energy-efficient way to cool household air in very dry climates. They operate by passing dry outdoor air over water-saturated pads. The water in the pads evaporates, reducing the air temperature by 15° to 40°F before it is directed into a home. They do not work as well during the more humid monsoon in Arizona and have largely been replaced over the last few decades in favor of air conditioners. During Keith’s childhood, playgrounds did not have built shade structures and no one carried water bottles. When it was hot, residents visited their local public pool, or if they were lucky they took a family trip to Justin’s WaterWorld or Breakers Water Park.

Keith measures his vehicle’s air temperature and the surface temperature of the street in Tucson, on July 17, 2023. Image by Ladd Keith.

Today, extreme heat is the talk of Tucson and the nation. Heat waves impacted much of the U.S. in July and brought record temperatures to parts of the Southwest. The Southwest experienced the warmest July ever–tied with 2003. This summer, Keith measured air temperature outside his vehicle of 111 degrees Fahrenheit and street surface temperatures of 172 degrees Fahrenheit in the city. Dry heat, in excess, can be just as harmful as humid heat. At 111 degrees Fahrenheit, dry heat feels like a giant industrial vise, painfully forcing from above and below. At 180 degrees Fahrenheit or more, skin contact with asphalt streets can cause a third-degree burn. In 2022, heat exposure caused 671 deaths across Arizona. In Phoenix, the heat is killing the saguaro cactus. The cactus is adapted to the desert, but even saguaros have limits.

Climate change threatens the survival of the giant saguaro cactus—symbol of the American Southwest. NOAA Climate.gov image by Anna Eshelman.

Keith, an expert in urban heat policy and planning, is an assistant professor in the School of Landscape Architecture and Planning and a faculty research associate at the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy at the University of Arizona in Tucson. He is hard at work helping communities large and small increase their heat resilience in a warming world. “Heat governance” establishes best practices for all levels of government to mitigate heat, or reduce urban heat, and manage heat, or coordinate, plan, and respond to chronic and acute heat risk. It establishes a stable system of accountability and responsibility in times of crisis.

Keith and his partners in the field lead the growing national media discussion on heat governance. He regularly speaks to outlets such as The Washington Post, The Christian Science Monitor, Associated Press, and America Adapts: The Climate Change Podcast. “Media coverage of extreme heat has grown each year, which has given me the opportunity to help raise awareness about the impacts of heat and how we can improve our heat planning and governance.” Thanks to his work in the public square, more and more Americans know that heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States. Americans are learning that heat stress is cumulative–meaning that it is critical to recover from the day’s exposure and cool down at night. The majority of Americans (72%) are at least “a little worried” their local area might be harmed by extreme heat.

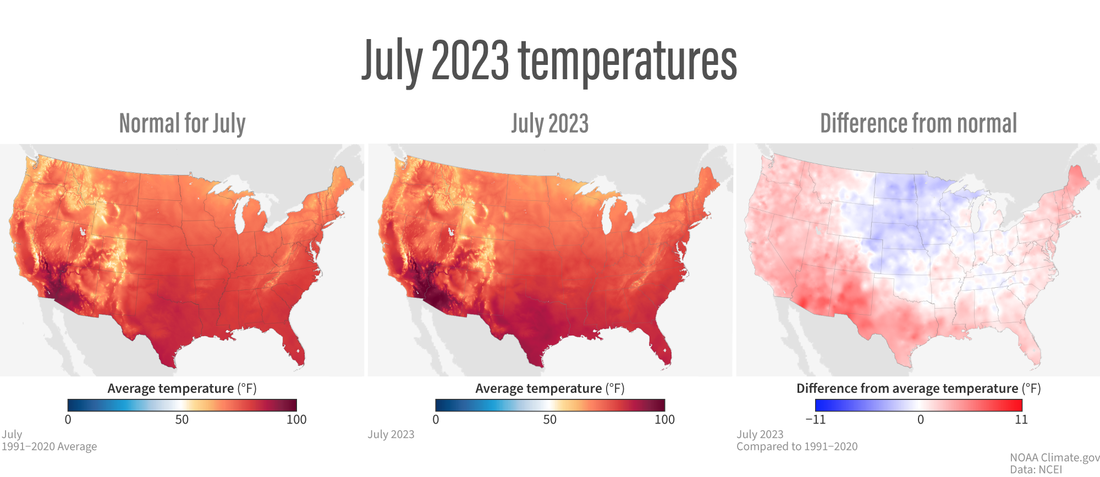

(left) Average July temperatures across the contiguous United States based on data from 1991-2020. (center) Temperatures in July 2023. (right) July 2023 temepratures compared to average. NOAA Climate.gov images, based on data from NOAA NCEI.

Behind his ambitious research enterprise is a simple hope: he wants his children to be able to make a life in Arizona, if they so choose. “While every community is at risk from extreme heat,” said Keith, “Arizona is truly on the frontlines of impacts and at the forefront of solutions. We have more work to do to keep our communities thriving for future generations.”

The rise of heat governance

Keith’s current research is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Today, multiple federal agencies set and influence policy on extreme heat, from planning for heat waves to studying heat illness and mapping urban heat islands. But the notion of heat governance is quite new. In fact, U.S. heat policy has historically been thin and fragmented. Policymakers have long failed to appreciate the severity and urgency of extreme heat. “Why isn't the national government thinking about heat?” wondered Keith, when he began studying climate change policy during his doctoral studies. “Heat is literally the fingerprint of climate change. Yet it is the last climate hazard that we're really starting to look at and think about seriously.”

For many decades, heat waves have stretched the resources of social workers, paramedics, doctors, and public health officials. The public sector has often responded to extreme heat on a short-term emergency basis without comprehensive planning or coordination for the long term. Cities have planned for and dedicated resources for earthquakes, droughts, wildfires, and flooding, but not heat–until a few years ago. The deadly Chicago heat wave of 1995 should have been a turning point in this regard; it raised national awareness of the consequences of lack of preparedness, but national action did not follow. "Many of our over three thousand U.S. counties have floodplain managers who are dedicated to protecting lives and property from flooding,” said Ladd Keith, “but we have only three communities with chief heat officers out of 19,000 communities in the United States."

One reason for extreme heat’s historically small public profile is that heat-related death tolls have been underestimated and underreported. For a long time neither the federal government nor the National Association of Medical Examiners developed a uniform definition of a heat-related death. The CDC’s current heat mortality numbers, moreover, are based on information reported on death certificates. Based on this data source, an average of 1,220 heat-related deaths occurred among U.S. residents annually (2019 –2021). But the true mortality burden is much higher because heat exposure is a contributing factor to deaths resulting from many causes, and heat exposure is not always listed on the death certificate.

An elderly woman faints from heat on New York City's Upper East Side in 2011. Photo from New York Daily News/Marcus Santos.

Another reason for its small public profile is that heat is hard to visualize. According to sociologist Eric Klinenberg, “Hurricanes, which generate the most expensive property damage as well as the most spectacular images, get the headlines in the United States.” “When heat comes, it’s invisible. It doesn’t bend tree branches or blow hair across your face to let you know it’s arrived,” says Jeff Goodell in The Heat Will Kill You First, a new book on the global heat health crisis. “The ground doesn’t shake. It just surrounds you and works on you in ways that you can’t anticipate or control.”

NOAA supports Keith’s early career

The Climate Adaptation Partnerships (CAP) / Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISA) program, managed by NOAA’s Climate Program Office, was one of the first federal programs that began funding research on heat and heat-health. The program has worked in this area since the early 2000s. In 2013, when Ladd Keith began his Ph.D. in Arid Lands Resource Sciences at University of Arizona, he met CAP/RISA researchers, such as Dr. Gregg Garfin and Dr. Dan Ferguson, who helped kick off his career in heat governance studies.

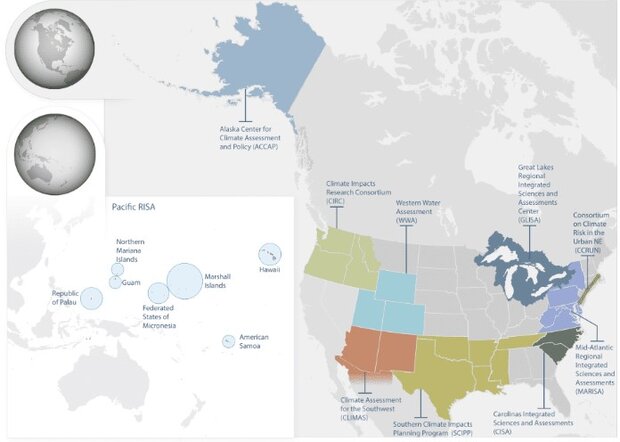

CAP/RISA is an applied research and engagement program that expands society’s regional capacity to adapt to climate impacts in the U.S. The CAP/RISA program supports sustained, collaborative relationships that help communities build lasting and equitable climate resilience. There are currently 12 active CAP/RISA teams covering regions across the U.S., including several Pacific and Caribbean islands. Although climate risks look different across these regions, the rapid and intense epidemic of extreme heat knows no borders. Swiftly rising average temperatures—as well as more frequent heat wave events—have established the social aspects of extreme heat as a defined research area for many CAP/RISA teams all across the country.

NOAA's Climate Program Office currently supports 12 active CAP/RISA teams covering regions across the U.S., including several Pacific and Caribbean islands. NOAA Climate.gov image.

Since 1998, the Climate Assessment for the Southwest (CLIMAS) has published research focusing on impacts of extreme heat on border communities, drought conditions, and the connections between heat, water resources, and energy. But with temperatures rising and extreme heat events increasing in frequency, recent research has shifted towards using data and information to create action plans and prepare urban, rural, and border communities across the Southwest for a hotter future.

Keith joined the Climate Assessment for the Southwest (CLIMAS) in 2016, when he earned a NOAA grant of $45,281 to conduct interviews and plan analysis on the state of urban resilience in Arizona and New Mexico. “My first research opportunity with CLIMAS helped demonstrate that while there was concern about extreme heat, city planning efforts for it lagged far behind planning efforts for drought, flooding, and wildfire. That led to my current focus on heat planning, policy, and governance.”

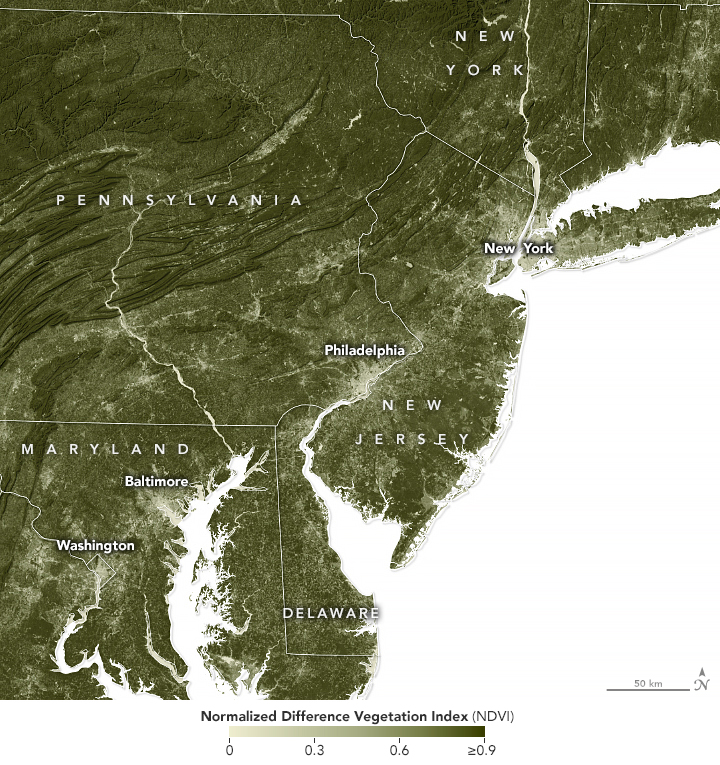

CLIMAS first funded Keith as a named investigator in 2017-2022, when he served as a co-investigator on several subprojects, and led one project titled "Evaluating the use of urban heat island and heat increase modeling in land use planning." The project focuses on Arizona and New Mexico, and examines the “urban heat island”, which refers to the fact that cities tend to get much warmer than their surrounding rural landscapes, particularly during the summer. This temperature difference occurs when cities’ unshaded roads and buildings absorb heat during the day and radiate that heat into the surrounding air. As a result, highly developed urban areas can experience day and nighttime temperatures that are 15°F to 20°F warmer than surrounding, vegetated areas.

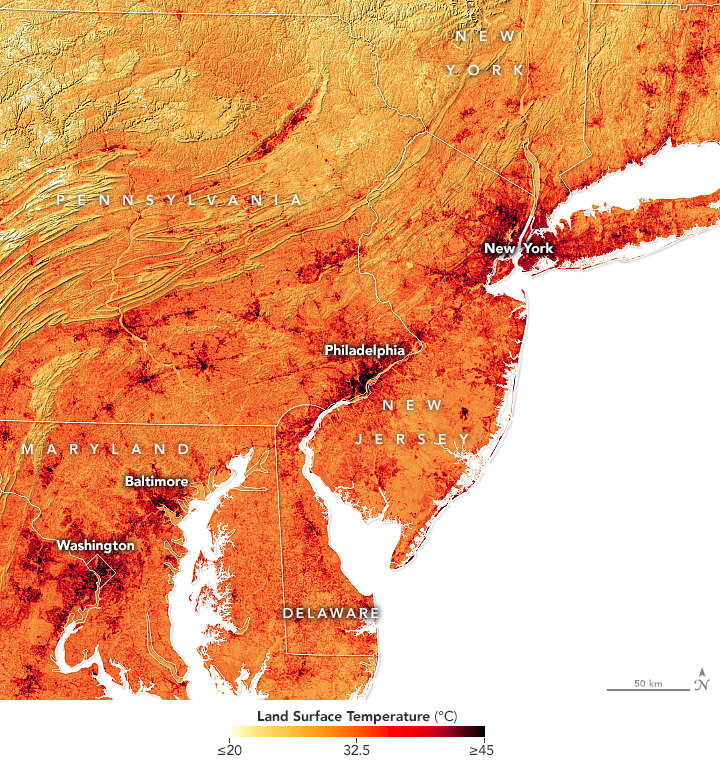

Click and drag slider to compare images. Paved surfaces and other urban infrastructure are hotter than nearby areas with trees and other vegetation, a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect. The maps above show the abundance of vegetation around several urban areas in the Northeast, as well as the average land surface temperatures. The sparsest vegetation (tan to light green) is associated with the hottest land surface temperatures (darkest red). The maps were made using data acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 from June 21 to September 22, 2019. Images courtesy NASA Earth Observatory.

“Although Arizona has historically been hot, we're also the fastest growing-state in the United States, which is worsening the urban heat island effect, " says Keith. “Poor planning in the past and climate change are fueling more record-breaking extreme heat events, which means that we are facing more dire consequences than ever before.”

Maricopa County, which encompasses five of the top ten most populous cities in the state of Arizona, just released their most recent heat death report. In 2021, there were 339 heat-related deaths—that figure jumped to 425 in 2022, a 25% increase. This year, the heat-related death numbers under investigation are 35% higher than they were at this point last year. Keith’s heat research seeks to help communities better address these increasing impacts from extreme heat.

Today, Keith leads the CLIMAS research program on heat resilience among rural, tribal, and border communities. One of his most recent CLIMAS-funded papers is titled, Urban heat governance: examining the role of urban planning. The study examined five U.S. cities’ approaches to heat-health resilience and identified opportunities to improve the use of climate information. The cities participating in the project were Tucson, AZ; Houston, TX; Baltimore, MD; Detroit, MI; and Seattle, WA.

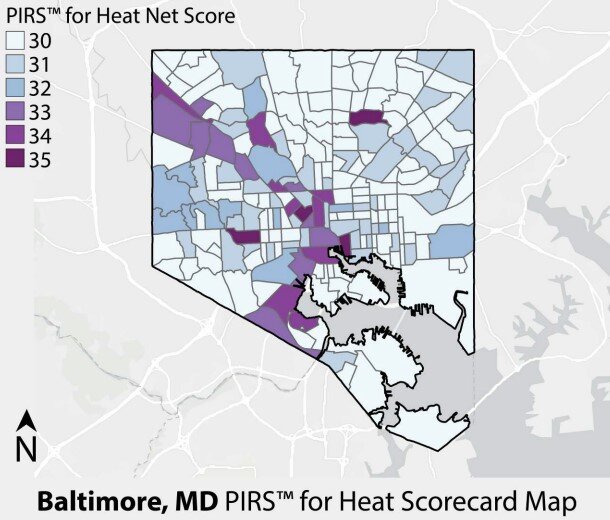

The findings from this study showed the need to to break down disciplinary barriers in heat planning. This led to the development of the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ (PIRS™) for Heat, funded by CAP/RISA and the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS). PIRS™ for Heat is an extension of the original PIRS™, and allows communities to analyze how heat mitigation policies are integrated across different plans and identify opportunities to better target heat mitigation policies in high heat risk areas. A free guidebook explains the rationale for plan integration provides a step-by-step guide for any practitioner or researcher interested in applying the methodology, includes a detailed and ready-to-go worksheet, and summarizes key plan integration findings from five communities across the U.S.

Heat net scores for each census tract in Baltimore, MD, with higher scores (darker colors) indicating strong policies on heat mitigation. Net scores ranged from 30 to 35 across the city. The highest scoring tracts tend to be in the downtown and the west side of the city. Map courtesy the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ (PIRS™) for Heat report.

Keith counts on partnerships with CLIMAS and other organizations to help make heat governance a national priority for the 21st century. “A key thing that I have learned from CLIMAS,” he said, “is the importance of co-produced research, or research that involves the intended end-users from start to finish. The co-production of science is a two-way street and helps lead to more useable research results and better engagement with communities and decision-makers.”

”While extreme heat continues to increase due to climate change, so is the interest in addressing it across all levels of government. The CAP/RISA program is essential to ensuring that communities of all sizes across the U.S. are better prepared for extreme heat.”

Sources

- Goodell, Jeff. The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2023.

- Klinenberg, Eric. Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. (2nd ed.) Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- NOAA interview with Ladd Keith, May 4, 2022.

- NOAA Interview with Ladd Keith, July 10, 2023.

- E-mail from Dr. Kristie Ebi, Professor, Global Health; Professor, Env. and Occ. Health Sciences, Univ. of Washington, July 28, 2023.

- E-mail from Ambarish Vaidyanathan, Senior Health Scientist, CDC, September 8, 2023.