In our previous post, we described how very unusual the temperature extremes have been across the United States so far in 2014. We talked about how, for any given half-year period, you might see a large part of the country experiencing warm extremes or cold extremes, but generally not both. By contrast, January-July 2014 set a record for having large areas of both temperature extremes.

Looking back at what the atmosphere was doing during this time period quickly reveals at least part of what was going on: the polar jet stream got into a serious rut.

The polar jet is a high-altitude, blisteringly fast wind that blows around Earth at mid- and polar latitudes. It dips into and out of the Arctic, weaving around the margins of shifting high and low pressure air masses. Starting last fall, the polar jet began repeatedly following a route over North America that took it over Alaska and western Canada, and then brought it swooping down like a roller coaster over the Great Plains and the Midwest. There it bottomed out and climbed steeply north.

The deep dip into the central United States—what meteorologists call a trough—fills with chilly, Arctic air. The places where the jet stream says high in the Arctic—called a “ridge”—allows warmer air to the south to stagnate.

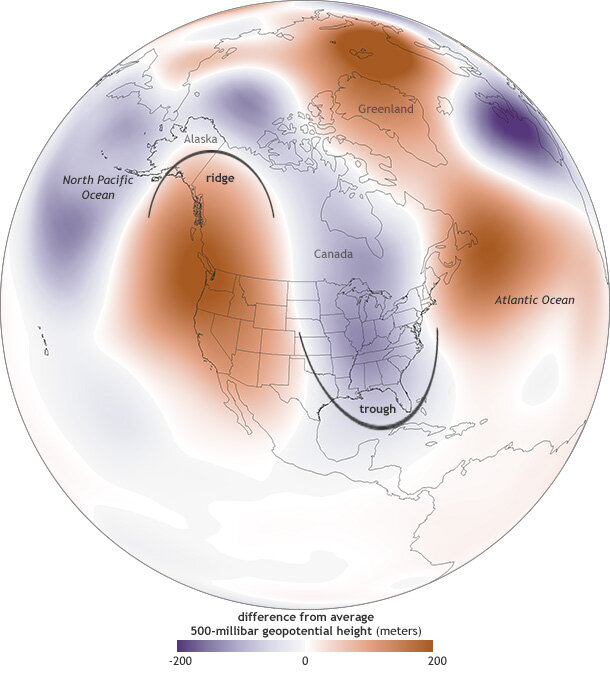

Difference from average pressure at 500 millibar (mb) pressure level January 14-21, 2014, linked to very exaggerated dips and bumps in the polar jet stream. In general, air pressure decreases with altitude. On this map, negative numbers mean relatively low pressure values typically found at higher altitudes existed up to 200 meters closer to the surface than usual; positive numbers mean relatively high pressure values typically found closer to the surface reached up to 200 meters higher in altitude than usual. Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on NCEP reanalysis data from NOAA ESRL.

It’s not that these ridges and troughs, these dips and bumps in the jet stream’s path, are uncommon. What’s unusual is for the dips and bumps to linger in the same place for months on end.

According to Weather Underground meteorologist Jeff Masters, “We have been stuck in this pattern of a trough of low pressure over the Midwest and a ridge of high pressure over the West coast since November of last year.” High pressure generally leads to warm and dry weather, which means the same jet stream pattern producing the temperature extremes also contributed to the lack of winter snow and rain in the West that extended California’s drought.

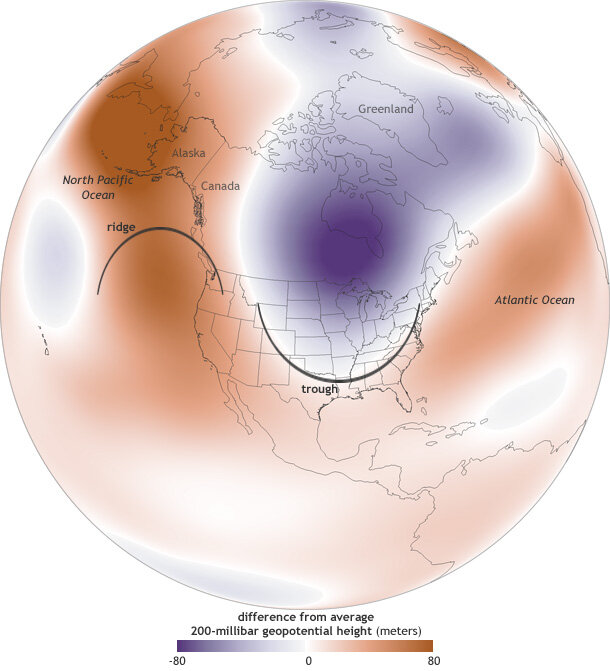

Difference from average pressure at 200 millibar (mb) pressure level from November 2013-July 2014. The polar jet stream repeatedly followed a path of steep ridges and toughs over North America during this period; the unusual configuration occurred frequently enough that it left a permanent impression on the average pressure patterns during the period. Unusually high pressure (orange) occupied the area beneath the ridge to the west, while unusually low pressure filled the trough over the central United States. These pressure anomalies were mirrored in the U.S. temperature extremes in the first half of 2014. Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on NCEP reanalysis data from NOAA ESRL.

It’s an unusually long—“ridiculously long”—time for the atmosphere to be stuck in such an extreme pattern, Masters says. “Normally, at least the changing of the seasons would disrupt these stagnant jet stream patterns, if nothing else did. But we’ve gone from fall, to winter, to spring, and now even into summer, and the jet stream didn’t budge.”

So what would have caused the jet stream to get into such a rut? Masters says researchers are investigating a few hypotheses—Pacific Ocean temperature anomalies, climate change, natural atmospheric dynamics—but there are no firm answers yet. Given the exceptionally long stretch of time we are talking about with the 2014 event, Masters thinks it’s probably multiple influences acting over different time scales, some long-term and some, like Typhoon Neoguri in the Pacific in July, short-term.

For California’s sake, we can hope the peculiar jet stream pattern breaks before the state’s wet season begins later this fall.